Let's Talk About that Anthropic Decision

Is it all doom and gloom for human creatives? Maybe not.

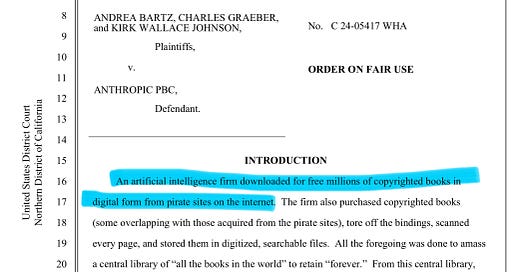

No doubt by this point in the day you have seen the headlines about the U.S. District Court’s June 23rd order (the “June 23rd Order”) in the matter of Bartz v. Anthropic PBC (US Dist. Ct. N.D. California Docket 3:24-cv-05417-WHA). In the abstract, the fact pattern is a familiar one by now for those who are following the copyright related litigation initiated by authors against the artificial intelligence developers: the developer copies legally protected works at scale without any license or payment to the rights holders, and uses those protected works to train software. Indeed the first sentence of the June 23rd Order says as much:

Since newspapers are not written for the creative industry or legal professional, many important details fall by the wayside and do not make it into the news articles. Let us dive into this.

The Parties

The Plaintiffs in this case are three authors: Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber, and Kirk Wallace Johnson. From the June 23rd Order:

Author Bartz wrote four novels Anthropic copied and used: The Lost Night: A Novel, The Herd, We Were Never Here, and The Spare Room. Author Graeber wrote two non-fiction books likewise at issue: The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder, and The Breakthrough: Immunotherapy and the Race to Cure Cancer. And, Author Johnson penned three non-fiction books also copied and used: To Be A Friend Is Fatal: The Fight to Save the Iraqis America Left Behind, The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century, and The Fishermen and the Dragon: Fear, Greed, and a Fight for Justice on the Gulf Coast. Plaintiffs Bartz Inc. and MJ + KJ Inc. are corporate entities that Author Bartz and Author Johnson respectively set up to market their works. Between them, these five plaintiffs (“Authors”) own all the copyrights in the above-listed works.

June 23rd Order, at 2.

The defendant in this case is Anthropic PBC, which is an AI software company. Anthropic’s core product is an AI app named Claude which, when prompted by a person, can respond with text that mimics human reading and writing. Claude is a $1 Billion business on an annual basis. Id.

The Conduct

Anthropic is alleged to have engaged in several discrete activities with protected works that requires examination. These are the details that were not reported on very well. What is being reported is basically a vanilla allegation that Anthropic used protected works to train the large language model upon which Claude is built. What is alleged to have happened is more complicated.

The Plaintiff alleges that Anthropic employees downloaded pirated copies of many (thousands and thousands) novels, including the novels written by the Plaintiffs, to train the large language model that Claude is based upon. The court refers to this set of activity as the “Training Copies”.

Secondly, the Plaintiffs are alleged to have purchased millions of physical print copies of the protected works, tore the covers off, and scanned the pages into a digital form, which then was manipulated and scanned. It appears from the June 23rd Order that the trial record supports the allegations. The court refers to this use as the “Purchased Library Copies”.

Anthropic’s stated purpose in the digitization of the purchased copies was to build a research library. Order at 14. It did so by combining both the Purchased Library Copies AND the pirated works (which the court later refers to as the “Pirated Library Copies”).

Remember that this case has not been decided on the merits so allegations are at this point ALLEGATIONS that have been construed in the light most favorable to the non-moving party (i.e. the Plaintiffs). The following is the type of allegation that will make human authors/musicians1 seethe with rage and contempt:

From the start, Anthropic “ha[d] many places from which” it could have purchased books, but it preferred to steal them to avoid “legal/practice/business slog,” as cofounder and chief executive officer Dario Amodei put it (see Opp. Exh. 27). So, in January or February 2021, another Anthropic cofounder, Ben Mann, downloaded Books3, an online library of 196,640 books that he knew had been assembled from unauthorized copies of copyrighted books — that is, pirated.

June 23rd Order at 2-3 (emphasis added by author).

In other words, the Tech Bros decided legality was too inconvenient so they took the faster path.

The subject of the June 23rd Order is whether the various alleged uses of the Defendants constituted fair use, avoiding liability under the Copyright Act. A quick refresher on that topic may be in order.

Fair Use Refresher

What is fair use? Fair use is a defense to a copyright infringement claim.

Fair use is, simply stated, a defense to a copyright infringement claim. This doctrine allows for, in certain, limited circumstances, the unlicensed use of copyrighted works.

The Copyright Act provides provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses — such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research — as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use.

Generally speaking, only a federal court after a copyright infringement case has been filed can really determine if one’s actions in using a copyrighted work constitutes fair use and is thus permissible. From a startup or entrepreneur’s standpoint, if you are in the educational space or publishing space involving artistic criticism, fair use becomes a significant debate at the office. For the purposes of this paragraph, “publishing” could include not only the written word but also video blogging and related content production.

There are four factors that courts will consider in determining if the unlicensed use of a copyrighted work constitutes fair use:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted

work.2

For the purposes of this case, the phrase “of a commercial nature” should loom very large in the analysis. What is the entire purpose of Anthropic’s activities? Anthropic’s purpose is to launch a commercial product which people would pay to use. This alone should have caused the court to rule against Anthropic. The court’s fair use analysis begins on page 9, line 22 of the Order.

What did the court actually rule in the June 23rd Order?

It is important to note that the Plaintiffs did not file a motion for summary judgment, and the June 23rd Order resulted from a motion for summary judgment filed by Anthropic. While the business press represented the June 23rd Order as a huge win for Big Tech, that is not necessarily the case. The court’s decision is much more nuanced than what is being reported. The Court’s Order provided:

Anthropic’s training use was fair use; AND

Anthropic’s digitization of the Purchased Library Copies was fair use; HOWEVER

the court denied Anthropic’s motion for summary judgment on the copying and digitization of the Pirated Library Copies.

The court further orders a trial “on the pirated copies used to create Anthropic’s central library and the resulting damages, actual or statutory (including for willfulness). That Anthropic later bought a copy of a book it earlier stole off the internet will not absolve it of liability for the theft by it may affect the extent of statutory damages…” June 23rd Order at 31.

Is the court foreshadowing a win for the Plaintiffs here? It certainly appears that way. The news organizations are reporting this order as though it is a home run for the tech companies, but the above quote certainly is at odds with that conclusion.

You can read the June 23rd Order below, including my annotations thereto:

The fact that I even have to write “human” here is baffling to me, but we are where we are.

17 U.S.C. § 107.

J. Bryan Tuk is the founder of Tuk Business & Entertainment Law, and the author of risk, create change: a survival guide for startups and creatives.